I like to write a few articles in my free time. Some have been published and some have not. Most of the articles are Ireland related and generally of a historical or cultural nature. I may be contacted through the email on this site.

Tuesday, November 8, 2016

Lime Kiln, Newbridge, County Dublin.

In decades gone by, lime was obtained from limestone which was heated in such kilns. the lime was used to make whitewash which was painted onto cottages and walls at least once a year. This example is at Newbridge near Donabate in North county Dublin.

Friday, October 28, 2016

The Death of Patrick Waters

CONNACHT TRIBUNE

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28, 2016

The Death of Patrick Waters

BY RÓNÁN GEARÓID Ó DOMHNAILL

Galway RIC man

was killed in Kerry

– and a century on

his body has never

been found

On Halloween evening 1920, a young

RIC constable from Galway vanished

in Tralee and his body was

never recovered.

Those who killed him and disposed of his

body never informed his family – and Patrick

Waters became one of what became known

as ‘the disappeared’.

Patrick Waters or Pádraig Ó Tuairisg as he

was known locally, was born on 15 May 1896

in Lochán Beag near Indreabhán in Connemara.

He came from a family of eight children,

five sons and three girls. According to the 1911

census, which lists him as a sixteen-year-old

scholar, he had a number of younger siblings.

By the time he enlisted in the RIC his occupation

was given as farmer.

Farmers in South Connemara were not

that big and a job in the RIC would have provided

a steady income with a pension after 25

years and financial support for his family.

Waters had limited options if he did not

want to farm the land, go to America or join

the priesthood.

Thus he went into Galway and was recommended

by District Inspector Hildebrand.

According to the RIC register, the original

of which is kept in the Public Records Office,

Kew, Surrey, he was appointed constable

with the number 69079 on 17 April 1917.

No promotions or punishments are

recorded and Tralee was his first and only

posting.

The RIC – unlike the police in Britain – were

armed and essentially the eyes and ears of

the British government.

Most of the rank and file members were

Catholic while the officers were Protestant.

They never served in their home county or

even that of their wives.

Things changed however when on 11 April

1919 the Dáil announced a policy of ostracism

of RIC men. There were now seen as agents

of the crown and traitors.

The War of Independence itself began in

1919 with the killings of two RIC constables,

Patrick MacDonnell and James O'Connell,

when they were shot by Dan Breen at Soloheadbeg,

County Tipperary.

Recruitment dropped and resignations increased.

The infamous Black and Tans, former

British soldiers now filled their ranks.

Those who remained in the force did so

out of a sense of loyalty to duty and some,

such as Glenamaddy man Jeremiah Mee,

worked with the IRA providing them with

valuable information.

In the last of week of October 1920, the IRA

HQ in Dublin ordered attacks on Crown

forces across the country.

This was in reprisal for the death of Terence

MacSwiney who died on hunger strike

in Brixton prison on 25 October and also for

Kevin Barry who was due to hang on 1 November.

The RIC patrolled in large numbers and

Waters would have been safe in his barracks.

His Achilles heel however was that he single

man far away from home and probably looking

to find a wife.

According to Ryle Dwyer in his book Tans,

Terror and Troubles - Kerry’s Real Fighting

Story 1913-23, both he and Ernest Bright were

lured to a house in Strand Street by two local

women, believed to be in the Cumann na

mBan.

The two men were confronted by IRA man

Paddy Paul Fitzgerald who was waiting at Gas

Terrace.

What happened next, I have pieced together

from different witness statements of

former IRA men, given to the Bureau of Military

History in the late 1940s and early 1950s

and made public in 2003.

As they were unarmed they had no choice

but to surrender. They were passed on to the

Strand Street company and according to IRA

man Michael Doyle, were shot later that night

at a spot at the end of the canal known as The

Point, on orders of Brigade staff

and Paddy Cahill as Brigade officer.

The RIC register for Waters states

that he died on 31 October and had been ‘kidnapped

and presumed murdered’.

The IRA never publically acknowledged

killing the two constables. All the Waters family

would learn is that their loved was sent to

Kerry where he was killed but they would

never have a body to mourn over.

When it became known that the constables

were missing, the Black and Tans unleashed

a reign of terror in Tralee in events which become

known as the Siege of Tralee which

lasted for nine days.

Several notices are put up around the town

declaring that unless the two RIC men were

returned by 10am on the 2 November terrible

reprisals would be unleashed.

A few days previously, two unarmed constables

in Ballylongford, James Coughlan and

William Muir had been taken by the IRA and

held for sixty hours until IRA HQ in Dublin

ordered their release.

The British authorities had threatened to

raze the town to the ground if they were not

released. Both were released though had

been severely beaten.

The RIC in Tralee were hopeful that by

threatening the local population, Waters and

Bright would also be released. They did not

know they were already dead and had been

secretly buried.

When the two constables never reappeared,

rumours began to circulate and it

was reported locally that the pair were

thrown alive into the furnace in Tralee Gas

Works, which was repeated in Richard Abbott’s

Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922,

written in 2000.

Another theory was that they were buried

in the canal near the house of the lockkeeper,

William O’Sullivan, who was a member of the

IRA Company involved in killing Waters.

His grandson told local historian Ryle

Dwyer in the mid-1990s that he believed that

the two constables were buried in the family

tomb at Clogherbrien graveyard just outside

Tralee on the road to Fenit.

When his grandmother died in 1926, his

grandfather was horrified at the idea of burying

her in with the two constables and she

was buried outside the tomb. This in my view

is the strongest theory of where Waters is

buried.

I went along to Clogherbrien graveyard

and discovered two O’Sullivan tombs. Beside

one was a cross corroborating this story

and the O’Sullivans were buried outside

their tomb since 1926. Jim

Herlihy, author of The Royal

Irish Constabulary - A Short

History and Genealogical

Guide believes that Waters

may be buried in Derravrin

bog in Lixnaw, close to Listowel.

Farmers Michael O'Connell

and Brendan Cronin

who want see the body

buried there given a

proper burial, claim it

is still located under a

crab tree.

Others such as

Helen O’Carroll, the director

of Kerry County

museum, with whom I

spoke, are sceptical of

this. Lixnaw is about 18

km from Tralee and to transport

a body such a distance

would have been very risky.

Clogherbrien on the other hand is in

close proximity to the canal.

In either event, the body of Waters is

one of the few never to have been recovered.

Patrick Waters was neither a nationalist

nor a unionist. He was a small farmer from

the rocky shores on Galway Bay trying to

make a living in difficult times and came

from a very similar background to those who

ended his life.

People get killed in wartime but it benefits

nobody to deny the family the corpse of their

loved one. I believe Patrick Waters is buried

at Clogherbrien – and maybe now, after

nearly a hundred years, it is finally time to

bring him back to Galway.

Rónán Gearóid Ó Domhnaill, from Galway

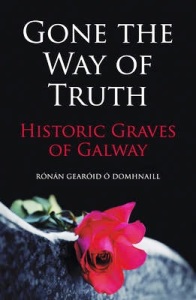

city and living in Dublin, is the author of Gone

the Way of Truth - Historic Graves of Galway

published by the History Press.

Tuesday, October 18, 2016

An Triail

Chonaic mé An Triail inné san Axis i mBaile na Munna. Ceann de na drámaí is fearr sa nua Gaeilge. Bhí rud éicint le rá ag an n-údar Máire Ní Gráda.

I went to see the Irish language drama An Triail yesterday. Written in 1964 and staged on condition that it would be a once-off. It proved controversial and Irish society itself was on trial during the performance. An synopsis in English is available here: http://www.gaelminn.org/triail/synopsis.htm

Wednesday, August 24, 2016

St. Doulagh’s Church

For several years now the North side of

Dublin has been my home and amidst the soulless suburban sprawl there are

traces of the past which have survived centuries of change. The little known 12th

century Church of St Doulagh’s in Kinsealy, just off the Malahide road is one

such gem and so much of the medieval period is represented. It is easily

recognisable by its stone roof and unusual shape. There are very few churches

with stone roofs which have survived the passage of time, Cormac’s Chapel at

the Rock of Cashel and St Kevin’s Kitchen at Glendalough being the few

examples. St Doulagh’s is however the only one in the country which is still

used for religious services and is under the stewardship of the Church of

Ireland. The visitor is greeted at the entrance by a sandstone cross which is

believed to date from around the 13th century. The choice of stone

was unusual choice of material as the local stone would be limestone.

For several years now the North side of

Dublin has been my home and amidst the soulless suburban sprawl there are

traces of the past which have survived centuries of change. The little known 12th

century Church of St Doulagh’s in Kinsealy, just off the Malahide road is one

such gem and so much of the medieval period is represented. It is easily

recognisable by its stone roof and unusual shape. There are very few churches

with stone roofs which have survived the passage of time, Cormac’s Chapel at

the Rock of Cashel and St Kevin’s Kitchen at Glendalough being the few

examples. St Doulagh’s is however the only one in the country which is still

used for religious services and is under the stewardship of the Church of

Ireland. The visitor is greeted at the entrance by a sandstone cross which is

believed to date from around the 13th century. The choice of stone

was unusual choice of material as the local stone would be limestone.  The

Church is named after Doulagh who lived in the 7th century but

little else is known about him as documents written about his life were

believed to have been destroyed in the 17th century. What is known

about him is that he was an anchorite. I wrote about anchorites in my book Fadó Fadó Tales of Lesser-Known Irish

History. They were common in the early Christian Church, especially in

Eastern Europe and the Middle East and were different to hermits as although

they also lived alone, they did not move about. Indeed, they never left their

cell and were very much anchored to it. They were walled in in a special

ceremony and depended on support from the outside world. In a reminder of their

mortality they dug their own graves in their tiny cell with a small spoon. The

cell had several small windows, one for food, another one looked onto the altar

and another one allowed them talk with the public. Anchorites were regarded as

living saints and people

came to them for advice and to ask them to pray for intercession. There were also anchoresses, usually widows or young

girls who wanted to escape an unwanted arranged marriage. St Doulagh’s has an

anchorite cell attached to it and these are relatively rare in Ireland. The few

other examples that exist are at Fore Abbey in Westmeath and at St Canice’s

Cathedral in Kilkenny. The church is divided into sections from different era,

the newest being from 1865. The walls of the oldest part of the church are

three foot thick. There is

an altar like tomb inside, believed to be the resting place of St Doulagh

himself. In the oratory there is a hole which is believed to cure

headaches. As you ascend the 15th

century bell tower, there

is an alcove known as a penitent’s cell. It is just long enough for a man to

lie down in but not high enough for him to sit upright. This was where the

monks lay for days as part of a punishment. It was also used by lay people and

according to one local superstition, if a pregnant woman rolls in it three

times, she will not die while giving birth. St

Doulagh’s also has a leper’s window or squint, designed for those afflicted to

see the altar and receive the sacrament without coming into contact with the

congregation. Leprosy was widespread in medieval

Dublin and hospitals such as the Hospital of Saint James on Lazar’s Hill now

Townsend Street were set up to fight the spread of it. Those afflicted went

there to die but as far as society was concerned they were already dead and

they lived a purgatory type of existence. The site also contains a holy well,

St Doulagh's Well, watched over by a white thorn tree. The well was a cure for

the eyes but it was also used for baptizing. Indeed, it is the only free

standing external baptismal font in the country and is covered by an octagonal

shaped building. In 1609, it was covered in beautiful frescoes, financed by the

Fagan family of Feltrim, a nearby village. The frescoes featured Saint Patrick,

SBridget, St Columcille and St Doulagh.

The

Church is named after Doulagh who lived in the 7th century but

little else is known about him as documents written about his life were

believed to have been destroyed in the 17th century. What is known

about him is that he was an anchorite. I wrote about anchorites in my book Fadó Fadó Tales of Lesser-Known Irish

History. They were common in the early Christian Church, especially in

Eastern Europe and the Middle East and were different to hermits as although

they also lived alone, they did not move about. Indeed, they never left their

cell and were very much anchored to it. They were walled in in a special

ceremony and depended on support from the outside world. In a reminder of their

mortality they dug their own graves in their tiny cell with a small spoon. The

cell had several small windows, one for food, another one looked onto the altar

and another one allowed them talk with the public. Anchorites were regarded as

living saints and people

came to them for advice and to ask them to pray for intercession. There were also anchoresses, usually widows or young

girls who wanted to escape an unwanted arranged marriage. St Doulagh’s has an

anchorite cell attached to it and these are relatively rare in Ireland. The few

other examples that exist are at Fore Abbey in Westmeath and at St Canice’s

Cathedral in Kilkenny. The church is divided into sections from different era,

the newest being from 1865. The walls of the oldest part of the church are

three foot thick. There is

an altar like tomb inside, believed to be the resting place of St Doulagh

himself. In the oratory there is a hole which is believed to cure

headaches. As you ascend the 15th

century bell tower, there

is an alcove known as a penitent’s cell. It is just long enough for a man to

lie down in but not high enough for him to sit upright. This was where the

monks lay for days as part of a punishment. It was also used by lay people and

according to one local superstition, if a pregnant woman rolls in it three

times, she will not die while giving birth. St

Doulagh’s also has a leper’s window or squint, designed for those afflicted to

see the altar and receive the sacrament without coming into contact with the

congregation. Leprosy was widespread in medieval

Dublin and hospitals such as the Hospital of Saint James on Lazar’s Hill now

Townsend Street were set up to fight the spread of it. Those afflicted went

there to die but as far as society was concerned they were already dead and

they lived a purgatory type of existence. The site also contains a holy well,

St Doulagh's Well, watched over by a white thorn tree. The well was a cure for

the eyes but it was also used for baptizing. Indeed, it is the only free

standing external baptismal font in the country and is covered by an octagonal

shaped building. In 1609, it was covered in beautiful frescoes, financed by the

Fagan family of Feltrim, a nearby village. The frescoes featured Saint Patrick,

SBridget, St Columcille and St Doulagh.  Unfortunately, they were destroyed by

Sir Richard Bulkeley, founder of Dunlavin, County Wicklow, on his return from

the Battle of the Boyne. Crowds assembled there for St Doulagh’s pattern day

every 17 November until they were suppressed by the clergy in the late 18th

century due to the drunken rowdiness associated with it. Right beside it is a

small pool known as St Catherine's pond with stone seating, which some believe

was used for baptising girls. St Doulagh’s can be reached using Dublin

Bus and is open Sunday afternoons. Admission is free though donations are

welcome. Parking is not available.

Unfortunately, they were destroyed by

Sir Richard Bulkeley, founder of Dunlavin, County Wicklow, on his return from

the Battle of the Boyne. Crowds assembled there for St Doulagh’s pattern day

every 17 November until they were suppressed by the clergy in the late 18th

century due to the drunken rowdiness associated with it. Right beside it is a

small pool known as St Catherine's pond with stone seating, which some believe

was used for baptising girls. St Doulagh’s can be reached using Dublin

Bus and is open Sunday afternoons. Admission is free though donations are

welcome. Parking is not available. |

| A murder hole at St Doulaghs |

|

| A 19th century bell |

|

| A cure for headaches |

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

The Rock of Cashel, County Tipperary

|

| A 19th century depiction of the Rock of Cashel |

|

| The seal of the Vicar's choral, a small choir who lived and worked at Cashel |

Monday, August 22, 2016

War monument, County Clare

A plaque on Lahinch promenade to commemorate the landing of an American plane here during the Emergency, as the Second World War was known in Ireland. The plaque was unveiled in the nineties and like so many others needs a touch of paint to make the inscription legible.

St Mary's Collegiate Church, Gowran, County Kilkenny

St Mary's Collegiate Church dates from the 13th century and makes a visit to Gowran worthwhile. The county of Kilkenny itself has medieval monuments in abundance. Like many medieval churches of the time, it contains battlements, as churches were often under attack from the native Irish. The Bruce ransacked the place in the 14th century. It is managed by the OPW and admission is free. The photos above show an early example of ogham and two Butler tomb effigies. They are similar to those at St Canice's Cathedral in Kilkenny City. there are several more graves of interest here and a catalogue of graves is available for purchase.

Sunday, August 21, 2016

Hiring Fair Statue, Letterkenny

The Hiring Fair. Until the middle of the 20th century, it was not unusual for children as young as ten to hire themselves out to farmers for the season. This statute is in Letterkenny, county Donegal and from here the labourers went as far away as Scotland. There were hiring fairs all over the country, even in Dublin. In Irish these labourers were often referred to as the spailpín fánach.

Saturday, August 20, 2016

Wednesday, August 17, 2016

War monument Dublin

The above stained glass window is on display in the lobby of St Andrews College, Blackrock, Dublin. It commemorates fallen pupils who fell in the Great War of 1914-18 and symbolises another aspect of Irish identity.

Plaque to Dunnes Stores strikers in Dublin

A simple plaque reminds shoppers of ordinary workers who were willing to stand up for something in which they believed, even if it cost them financially. The above plaque is located on Henry Street.

Penal Cross

In the 18th century the Catholic church was suppressed in Ireland. From this time, the penal cross emerged. Note the narrow arms, designed so that the cross could be easily hidden up a sleeve. This example is from the Ulster Museum in Belfast. Other remnants of this times are mass rocks, an example of which also features on this blog.

Monday, August 8, 2016

Memorial to Merchant Seamen lost at Sea, Limerick City

I came across this monument in Limerick city. In Limerick, all Limerick who fell in conflicts are remembered and not just the select few. A few hundred metres away is also a monument to the sons of Limerick who fell in the world wars.

Thursday, July 28, 2016

Fairy Tree or Rag tree at Leenane.

A much abused fairy tree outside Leenane on the N59 overlooking Killary Harbour. When I was there, toilet paper, among other things, was hanging from it as well as other trees close by. Sad to see our culture being disrespected like this.

Wednesday, July 13, 2016

Gone the way of Truth review

The following Review was published in The Tuam Herald today (13 July 2016) Míle buíochas a Ruairí.

Check out more posts from Ruairí on his blogspot at:

https://bunosc.wordpress.com/2016/07/13/

Check out more posts from Ruairí on his blogspot at:

https://bunosc.wordpress.com/2016/07/13/

The Great Leveller

Rónán Gearóid Ó Domhnaill, whose mother’s family hail from Dunmore, is something of a polymath. He has great fluency in many aspects of Irish and German language and literature after many years in Europe. He works now as a secondary teacher in Dublin, from where he blogs as An Múinteoir Fánach; writing regularly on diverse aspects of history and folklore. He has published a number of books already; a collection of Irish legends in German, and more-recently Fadó: Tales of lesser known Irish history (2013) which covers intriguing and forgotten stories from around the country; body snatchers, priest catchers and female pirates.

His latest book Gone the Way of Truth: Historic graves of Galway is a return to his roots. The book is not an exhaustive list of all Galway’s graveyards, but rather a romp through some of the county’s most interesting burial sites and a look at some lesser-known people who are buried in them. The book covers Galway city and is thereafter divided four ways, to give a wide insight into the county’s graveyards; north, south, east and west. A concluding chapter covers Galway people buried outside their native county. In terms of north Galway, Ó Domhnaill returned to give a great insight into the ‘old’ Dunmore graveyard. He also spends some time discussing the celebrated Clonberne mausoleum and Temple Jarlath. The author’s extensive research can be seen in a knack for concentrating on those aspects of Galway funerary practices; inscriptions, images and other unusual features that have not received attention in previous surveys. In doing this he manages to bring to life long-forgotten and more recent stories and people in a way that is very human; the carving from the Temple Jarlath monument of a man holding his wife’s hand while she is dying is especially poignant. He is not afraid to tackle tricky topics either, makes extensive mention of the many ‘cillíní’ throughout the county and reminds his readers of their complex post-Reformation origins, that belie their having been simply a place for the unbaptised. He handles the recent ‘Tuam Babies’ story with tact and wisdom.

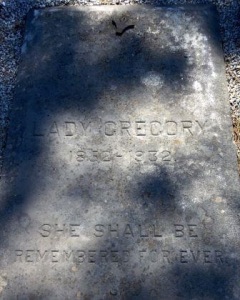

His extensive coverage of the Bohermore Cemetery in Galway is very valuable and makes it clear that it could well be described as Galway’s version of Glasnevin. If there is ever any doubt that death is the great leveller; of rich or poor, young or old, Catholic or Protestant, lord or tenant, it can be seen in Bohermore. The city’s original burial site at Fort Hill was overcrowded by the post-Famine era and so the city chose Bohermore as its new site in the early 1870s. The site is on an impressive height overlooking the city. It contains two mortuary chapels; Protestant and Catholic, Here, many of the revivalists and rebels currently being commemorated were laid to rest; Tomás Ó Máille, Pádhraic Ó Conaire and Micheál Breathnach, along with Galwegians who fell in the First World War. Here too lie Lady Gregory, Walter Macken, George MacBeth, and even William ‘Lord Haw Haw’ Joyce. Readable and richly-illustrated, Rónán Ó Domhnaill’s is a great guide to the work of the ‘great leveller’ in County Galway.

Saturday, June 18, 2016

The Cillín

The cillín forms part of silent grief which was only really

was discussed within the last years. There is a cillín in every parish, or

rather between every parish, in the country. Many have been erased from the

landscape, while others remain as a silent memory to a less compassionate era.

I have photos of monuments to the cillín in Gone

the Way of Truth. I came across this poem by Derry O'Sullivan while

watching a documentary about the Oileán na Marbh, the island of the dead, which

served as a cillín in Donegal. This poem, written in Irish with an English

translation after it, is about a cillín in Cork.

Saolaíodh id bhás thú

is cóiríodh do ghéaga gorma

ar chróchar beo do mháthar

sreang an imleacáin slán eadraibh

amhail line ghutháin as ord.

Dúirt an sagart go rabhais ródhéanach

don uisce baiste rónaofa

a d'éirigh i Loch Bó Finne

is a ghlanadh fíréin Bheanntraí.

Gearradh uaithi thú

is filleadh thú gan ní

i bpáipéar Réalt an Deiscirt

cinnlínte faoin gCogadh Domhanda le do bhéal.

Deineadh comhrainn duit de bhosca oráistí

is mar requiem d'éist do mháthair

le casúireacht amuigh sa phasáiste

is an bhanaltra á rá léi

go raghfá gan stró go Liombó.

Amach as Ospidéal na Trócaire

d'iompair an garraíodóir faoina ascaill thú

i dtafann gadhar de shocraid

go gort neantógach

ar an dtugtar fós an Coiníneach.

Is ann a cuireadh thú

gan phaidir, gan chloch, gan chrois

i bpoll éadoimhin i dteannta

míle marbhghin gan ainm

gan de chuairteoirí chugat ach na madraí ocracha.

Inniu, daichead bliain níos faide anall,

léas i Réalt an Deiscirt

nach gcreideann diagairí a thuilleadh

gur ann do Liombó.

Ach geallaimse duit, a dheartháirín

nach bhfaca éinne dath do shúl

nach gcreidfead choice iontu arís:

tá Liombó ann chomh cinnte is atá Loch Bó Finne

agus is ann ó shin a mhaireann do mhathair,

a smaointe amhail neantóga á dó,

gach nuachtán ina leabhar urnaí,

ag éisteacht le leanaí neamhnite

i dtafann tráthnóna na madraí.

You were born dead

and your blue limbs were folded

on the living bier of your mother

the umbilical cord unbroken between you

like an out-of-service phone line.

The priest said it was too late

for the blessed baptismal water

that arose from Lough Bofinne

and cleansed the elect of Bantry.

So you were cut from her

and wrapped, unwashed,

in a copy of The Southern Star,

a headline about the War across your mouth.

An orange box would serve as coffin

and, as requiem, your mother listened

to hammering out in the hallway,

and the nurse saying to her

that you'd make Limbo without any trouble.

Out of the Mercy Hospital

the gardener carried you under his arm

with barking of dogs for a funeral oration

to a nettle-covered field

that they still call the little churchyard.

You were buried there

without cross or prayer

your grave a shallow hole;

one of a thousand without names

with only the hungry dogs for visitors.

Today, forty years on

I read in The Southern Star --

theologians have stopped believing

in Limbo.

But I'm telling you, little brother

whose eyes never opened

that I've stopped believing in them.

For Limbo is as real as Lough Bofinne:

Limbo is the place your mother never left,

where her thoughts lash her like nettles

and The Southern Star in her lap is an unread breviary;

where she strains to hear the names of nameless children

in the barking of dogs, each and every afternoon.

Translated

from the Irish by Kaarina Hollo

Thursday, June 16, 2016

Tralee Museum

At first glance the town of Tralee does not really look as if it is more than 200 years old, a market town. It has however a much older history though sadly the medieval town was raised to the ground during rebellions against the English in the 16th century. The picture above was taken in the town's very fine museum which illustrates among other things, Tralee's medieval past. It shows a mercenary soldier, a galloglass holding his claymore.

Sunday, June 12, 2016

Sculptures of Lynch's Castle, Galway City

Lynch's Castle is on Shop Street in Galway city. In the 17th century, all of the tribes, the merchant families who made Galway a wealthy city, had similar castles. Today, only this and Blake's Castle, close to the old medieval quay remain. Lynch's castle has a strange effigy of an ape and a baby. According to legend, the animal saved the baby's life when a fire broke out in the castle. Note the Tudor coat of arms above the effigy. Galway was until 1916 a city very much loyal to the British crown.

RIC Crest

An example of an RIC crest from Tralee RIC barracks. The force policed the island of Ireland, becoming the RUC (later PSNI) in Northern Ireland and the Garda Síochána in the Free State (later Republic of Ireland) post 1922. Unlike policemen in Britain, the RIC was an armed forced and the eyes and ears of the the British establishment in Ireland. The crest is on display at Tralee Museum.

The Casement Brigade

A rare picture of the Casement Brigade. The term 'brigade' is perhaps inappropriate as it only ever amounted to a handful of members. The picture forms part of an excellent exhibition at Tralee Museum.

Saturday, June 11, 2016

Joe Howley Monument, Oranmore

A monument to Joe Howley of the IRA who was shot dead on arrival at Broadstone Station, Dublin in 1920. His grave is located behind the old church in the village.

Sean Ross Abbey, Roscrea

The grave of Michael A Hess (1952-1995) made famous in the movie Philomena, a film based on the book The Lost Child of Philomena Lee: A Mother, Her Son, and a Fifty-Year Search by Martin Sixsmith.

Thursday, June 2, 2016

Mass Rock, Galway City

During the Penal Laws the Catholic Church was forbidden in Ireland but it did not put a stop to people practicing their religion and they gathered at remote spots to celebrate mass. This example shows a cross on top of the 'Sliding Rock' at Shantalla.

The Grave of Michael Collins

The grave of Michael Collins at Glasnevin in Dublin is one of the most visited graves in the cemetery. Fresh flowers are placed there weekly. When the gravestone was erected in 1940, only one mourner, his brother, was allowed to attend. The then Taoiseach Eamon DeValera did not want to attract a crowd.

Gone The Way of Truth Review

Tom Kenny, writing in his Old

Galway column of The Galway Advertiser has mentioned my latest book.

In the second half of the 19th

century, the overcrowded condition of the graveyards of Galway was an issue

which faced the Town Commissioners. At a meeting in mid-April 1873, one person

mentioned that in the previous 30 years, almost two and a half thousand burials

had taken place in the little cemetery in The Claddagh, largely as a result of

the Famine and its aftermath.

Fort Hill was also overcrowded

and the committee there favoured the purchase of a three acre extension to the

graveyard, but were afraid that the three acres might not be enough.

Among the sites being examined

was one outside the immediate city area on Bohermore. The Bishop, Dr McEvilly,

wrote a long letter of recommendation to the Commissioners, at the same time

arguing against the Fort Hill idea. It was this letter which was largely

responsible for the decision to site the cemetery in Bohermore. The site was

bought from the board of the Erasmus Smith School. The older cemeteries in

Galway with their ancient graves were to be closed. This gave rise to some

discussion as to the condition of the graveyards in the city and in the

surrounding area. Cattle and sheep were allowed to graze on some of them. The

establishment of this new cemetery, which opened in 1873, was aimed to bring

order and control into the whole question of interment and to give dignity to

the last resting place of many Galway citizens.

The cemetery has two mortuary

chapels, the western one is reserved for Catholic usage, the eastern one for

Protestant usage. The Victorians liked to make memorials as ostentatious as

possible, often with classical symbols like urns or columns, but people began

to wonder about the suitability and cost of such monuments and after World War

I and so much loss of life, the public attitude to ostentation and decoration

was frowned on.

There are a number of literary

people interred in the ‘new cemetery’ as it is still known, Lady Gregory,

Pádraic Ó Conaire, Walter Macken, Arthur Colahan, George MacBeth, and William

Joyce. There are 17 Commonwealth burials from the 1914-18 war there, and three

from the 1939-45 period, and also some of those who were killed in the KLM air

disaster.

All this information and much

more can be found in a new book entitled Gone the Way of Truth, Historic Graves

of Galway by Rónán Gearóid Ó Domhnaill. This profusely illustrated volume is a

valuable exploration of an underexplored part of our heritage and features

graveyards from all over County Galway. Graveyards may be associated with

morbidity but they can also be interesting places to explore and provide us

with a window on our past. This book, which is published by History Press,

certainly does that. In good bookshops at €18.

Tuesday, May 17, 2016

Letterfrack

Located in the woods behind the local church at Letterfrack is a cemetery which is a brutal reminder to a crueler forgotten past. It is the final resting place of boys as young as four who died far home at the Industrial School, a type of Gulag run by the church and supported by the state. Read about those interred here in my book "Gone the Way of Truth Historic Graves of Galway".

My book will be launched in Charlie Byrnes, Galway City on Friday 20 May at 6pm sharp. All are welcome.

Tuesday, May 10, 2016

Fadó is still available!!

Just to let you guys know, my two previous books are still available from the following sites:

http://www.troubador.co.uk/shop_booklist.asp?s=fado%20tales%20of%20lesser%20known%20Irish%20History

From Kennys, one of the biggest independent bookshops in Ireland:

www.kennys.ie

and books.ie at

http://www.books.ie/catalogsearch/result/?q=fado

Why are they no longer available in bookstores? The problem is that although they sell well, they are self-published which means I have to pay for their publication. This is still poorly regarded in some circles but most authors in the 19th century were self-published. Because I have to pay for their publication, there is only a certain amount I cannot afford to print and cannot therefore supply a large market.

http://www.troubador.co.uk/shop_booklist.asp?s=fado%20tales%20of%20lesser%20known%20Irish%20History

From Kennys, one of the biggest independent bookshops in Ireland:

www.kennys.ie

and books.ie at

http://www.books.ie/catalogsearch/result/?q=fado

Why are they no longer available in bookstores? The problem is that although they sell well, they are self-published which means I have to pay for their publication. This is still poorly regarded in some circles but most authors in the 19th century were self-published. Because I have to pay for their publication, there is only a certain amount I cannot afford to print and cannot therefore supply a large market.

Monday, May 2, 2016

War of Independence Grave in Galway

The grave marker for Cecil Blake, late of the RIC. Read about him and other interesting graves in my latest book Gone the Way of Truth.

Sunday, May 1, 2016

post mortem photo on a tree in Kildare

Post mortem photos are quite rare in Ireland.this one was on a tree at a holy well.go ndéana Naomh Bríd trocaire uirthi.

Airiú, agus a leanbh ó!

Goidé a dhéanfaidh me?

Tá tú ar shiúl uaim.

Agus airiú, agus anuraidh

níl duine ar bith agam.

‘S airiú, agus me liom féin.

Dá mbeithea go mocha gam!

Agus och! Ochón airíu gan thú

Alas, my child!

What will I do?

You are gone from me.

And alas, since last year I’ve no one.

And alas, I’m all alone.

If you could be with me again soon!

Ach och!alas-without you!

An old Irish Caoineadh/lament

Sunday, April 3, 2016

Gone the Way of truth- Historic Graves of Galway has now been published. Sample a few pages here:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Gone-Way-Truth-Historic-Graves/dp/1845889045/ref=sr_1_sc_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1459702405&sr=8-1-spell&keywords=Gone+the+way+of+ttruth

Available in all good bookshops nationwide.

Details about the launch to follow.

Saturday, February 6, 2016

My latest book

Due out in April 2016. Available in all good bookshops. More info to follow as publication date approaches. It is already available to pre order on amazon.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Gone-Way-Truth-Historic-Graves/dp/1845889045/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1455110894&sr=8-2&keywords=Gone+the+way+of+truth

Gone the Way of Truth is a journey through Galway’s rich and varied past illustrated by graves of note. The gravestones themselves are monuments to people who once walked the streets and bohreens of Galway. They formed the very fabric of what it meant to be a part of this historic county.

The author has travelled the city and county extensively in the course of his research, discovering the resting places of, amongst others, musicians, poets, the last President of the League of Nations, saints and those who have shaped the course of Irish history. What emerges is a valuable exploration of an underexplored part of our heritage.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)